I am a writer. I have long had a habit of daily writing. Carrying a notebook around comes naturally to me. Prior to my cancer diagnosis, my writing had mostly been poetry, fiction, and essays. I had also done some work as a technical writer.

For the next year, I would fill multiple notebooks with details that I’d never thought to track: calories and proteins consumed, water intake, appointments, medications and side effects, more medications and more side effects, recommendations and remedies for side effects, notes of what the doctors and nurses said. These details became the focus of my daily life. Soon they became the only thing I wrote; they became my lifeline.

As I attempt to share my story, I am glad to have these notes for reference. In the beginning, they are neat and organized. Later, they become hard to read, both physically and emotionally. Often, I am struck by the recognition that, as my treatment progressed, as I became sicker and sicker, weaker and weaker, the notes too began to suffer. I find pages without dates, progressively sloppy writing, some unintelligible scribbles, and crossed out mistakes.

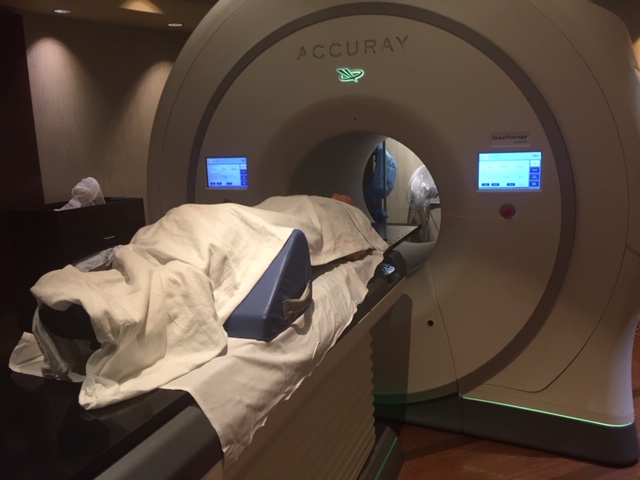

Radiation Therapy

My first radiation treatment was on Wednesday, December 4. My weight was 145.5 pounds. I’d already lost over 5 pounds since my surgery. That day, I consumed 2027 calories, 68 grams of which were protein, and drank 56 oz of water. During the day, I took Tylenol twice, for the residual pain from my surgery.

The radiation would burn my mouth and throat. The pain would get progressively worse. I knew this. My intention was to avoid prescription pain medication as long as possible, fully aware of their addictive nature. But by December 19, I would be taking Hydrocodone.

The radiation treatment was to be five days a week for seven weeks. This was more than the Cancer Board had initially recommended, which had been five to six weeks.

One to two weeks might not sound like much. But this meant five to ten more radiation treatments. Think about it. Radiation is used to shrink and eradicate cancer. But radiation also causes cancer. I was asked to sign multiple documents acknowledging that I knew and accepted the risks.

So here I was between a rock and a hard place. And it was about to get a lot harder.

Coping with The Procedure

There would be two technicians administering each radiation treatment. They verified each other’s work to avoid mistakes. If the radiation is administered incorrectly, it can miss the intended target while damaging otherwise healthy areas.

The room was dark and cold. The table where I lay was hard and narrow. The technicians helped me position myself on my back, my head in the precise spot pointing toward the machine that would deliver the radiation, a triangular cushion under my knees for comfort. They covered me with blankets for warmth.

Then came the mask. This was the hard plastic mold that had been made to fit my face, neck and shoulders exactly, a devise to keep me from moving during treatment and to help them target the radiation. It fit like a glove. I was about to find out that this was no glove. Gloves are comfortable. Gloves give.

A technician positioned the mask precisely. I could breathe through my nose. I could open and close my eyes, but not my mouth. No movement. I didn’t expect it to be comfortable, but I couldn’t know the horror of what came next until it happened.

I heard the click, click, click as the technician secured the clamps that would hold me in place throughout the radiation. With each click, the mask became tighter and tighter, pressing my skin against the bones in my cheeks and forehead, pushing my shoulders into the table. I panicked. I waved my hands at the technician, who released the clamps immediately and lifted the mask.

She asked if I was okay. I explained that I wasn’t expecting to be fastened down so tightly, to be restrained. I took a few deep breaths to calm myself. I realized I’d only been told the mechanics of the procedure, that I had to remain perfectly still, that the mask had been made to help target the radiation. No one talked about the emotional aspect. The fact of being physically restrained, shoulders, neck and head.

I imagined how someone with a previous trauma of being violently held down against their will might respond. I am fortunate to have never suffered such violence, but even so, I had panicked. I shared this thought with the technician. Yes, she informed me, some patients need sedation. I wondered at the nonchalance of her response.

No one had prepared me mentally. This is just one of many examples I would find throughout my treatment where the system and the procedures take precedence over the patient.

Now that I knew what to expect, I was ready to proceed. Ready, but not eager. I needed to find a way to keep myself calm while physically restrained. So, I decided to try meditation. In time, this meditative practice would evolve into a conversation with my cancer.

Chemotherapy

Though radiation therapy was under way, I still wasn’t entirely convinced that chemotherapy was necessary. Remember, not all doctors agreed on this point. (see My Cancer Journey – Part 2) The CT scan had, however, raised some questions in the mind of my medical team.

The surgery had removed my left tonsil. The right tonsil had shown no outward signs of being problematic. The bright spots on the CT scan, indicating cancerous lymph nodes, were also only visible on the left side. However, the scan showed an undefined, blurry area on the right side of my throat. For this reason, and in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, the team recommended chemo therapy. Though they never told me, I suspected they were erring on the side of caution.

My daughter and I had discussed my options. Ultimately, we decided that if the treatments didn’t work to eradicate the cancer, at least we would know we’d done all that we could. On December 13, I had my first Chemo treatment.

When I arrived at the clinic, I was asked to sign two forms, one acknowledging my consent for the hospital to treat and another for consent for the doctor to treat. These are pretty standard forms, usually a part of the patient check-in process. This would be the routine throughout my treatment.

Before each chemo session, my blood pressure and temperature were taken, and blood was drawn in order to check complete blood count (e.g. calcium, magnesium, potassium, etc) as well as organ function (such as kidneys and liver). During this process, on my first visit, the oncologist’s nurse arrived with another form requiring my signature. This was a generic form on which she had written Cisplatin in the medication section at the top, along with the dose, and the frequency (weekly with radiation).

There were ten generic items listed below the medication section, one of which (number 8) had been crossed off. Number eight referred to oral/pill form. My therapy would be administered intravenously. The other items were applicable to most/all other patients regardless of type of cancer or drug to be administered, generic. Below is a summary:

- The intent is to cure the disease

- Chemotherapy is not guaranteed to achieve the desired intent

- I give my consent to receive the medication

- I have been provided data sheets listing the drug’s side effects

- The physician and his/her staff have explained potential side effects

- The medication will be given through IV

- I have had the opportunity to discuss concerns with my doctor

- I accept the risks

- I can withdraw my consent and stop at any time I wish

After I signed the form, the nurse handed me a six-page printout of information about the drug Cisplatin. The information had been printed off the internet that day. The URL and date were clearly displayed across the bottom. Some of this information was new to me. It had not been discussed with the doctor. But by the time I had a chance to read the pages, I was already deep into the process, hooked up to the IV that would deliver fluids and drugs. And, I had already signed the forms.

If this sounds familiar to you, it’s probably because of what you just read above. For your convenience, I’ll repeat it here: This is just one of many examples I would find throughout my treatment where the system and the procedures take precedence over the patient.

And, to repeat what I shared in Part 3: Getting a cancer diagnosis is a scary thing. Treatment can be brutal and life altering. The doctors are eager to get to work on your case. Maybe a little too eager?

To this day, I wonder. If I had been given all the information I have today, would I have made the same decision? If I had been given more time, if I had taken more time and done more research, would I have agreed to chemotherapy?

The Participant Patient

You may remember that my CT scan showed a blurry, undefined area on the right side of my throat. Neither the radiologist who read the scan, nor the doctors, knew for sure what it was. I asked if it could be residual damage – bruising, irritation, or injury from my surgery – an area that hadn’t yet healed. The surgeon and the oncologist both agreed that was a possibility.

Because of this, and because one of the doctors I’d consulted had been adamant that chemotherapy was not needed (see Part 1), I still had doubts. And, because of my doubts and questions, the radiation oncologist ordered a biopsy.

The biopsy was done on December 17, the day of my tenth radiation treatment (25 left to go). The results were negative; no cancer on the right side. With this additional data, the radiation oncologist was able to adjust my treatment to better target the diseased area on the left, without doing further damage to the healthy tissue on the right. This only happened because of my questions, and the resultant biopsy.

This is not meant to be a criticism of the system or the people involved in treating my cancer. This is a reminder that you can and should be a participant in your care. Your healthcare team can’t know your concerns unless you voice them.

In his book Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, Dr. Atul Gawande writes about his experience as an oncologist, a variety of patients and their choices, and his own father’s life decisions as his father’s cancer progressed. Gawande advocates for the patient’s voice, the desires of the individual. I highly recommend his book.

Always ask for copies and read everything you sign. Ask questions and take notes. Participate in your care.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned. There will be more coming soon about My Cancer Journey. Feel free to leave a comment or question.

This is so good, in every way. The details are amazing. Your journaling really helped remind you of these details most of us forget or struggle to remember, especially just how exhausting cancer and the treatment can be. I have to reinforce your suggestion regarding “Being Mortal”. It is one of the best books I have ever read. He has a U-tube video we use in our “Honoring Your Wishes” program in our church to encourage people to make their wishes known and to complete advance directives….making end of life decisions now and including their families in these decisions. At any rate, this kind of writing is so needed. Great job, Shirley. Hope you are feeling strong and healthy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading. And thank you for your comments. I’m feeling well, grateful for my health and my journals. So much becomes a blur as we get distance and leave it in the rearview mirror.

LikeLike

Shirley, I feel like i am there with you as you are listening to the doctors around you, and following their instructions which is what we are taught to do, while you are also listening to some inner voice that has your unique angle on the situation. Is there room in our system for both voices?

The system works most efficiently when the patient doesn’t ask questions, and your story of the six pages about the drug is a great example of this. But it is the questioning patient who grows all of us: you digging in for more information on the right tonsil; you halting the technician about the mask clamps.

There are moments when i gave consent to doctors, blind consent, because i believed they could magically change a situation. In reflecting and questioning these decisions, in the swirl of regret that has gripped me at times in my life, I have grown into who I am today.

Keep sharing your journey with us so that we can grow with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind words. I think you are right. We are not taught to question our healthcare providers. And the curious/questioning patient is not built into the system. Some might see it as a disruption. But I believe that if we all continue to work on it, we can change the expectations, so that it’s not an either/or but a yes/and. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike